Looking for Young John Stahl: Some Biographical Mysteries Unravelled

An undoubted highlight of the 37th Pordenone Giornato del Cinema Muto in October 2018 was the screening of nine of the twelve surviving silent films of John M Stahl (with a tenth, The Woman Under Oath, shown in a short Stahl sound film programme at the Bologna retrospective a few months earlier). October 2019 should complete Pordenone’s exhibition of all Stahl’s surviving silents with the showing of The Woman Under Oath, One Clear Call and Why Men Leave Home, and a restoration of the one reel of The Wanters that survives. To historians of early Hollywood and silent cinema 2018 was, as one major expert in these areas, enthusiastically proclaimed, “The Year of Stahl”. And there is no doubt that Stahl’s recent profile, so low compared with his renown in the 1920s and 1930s, has been significantly raised by recent activity.

Part of this activity was a book edited by Charles Barr and myself, The Call of the Heart: John M. Stahl and Hollywood Melodrama (John Libbey Publications, 2018), with essays on every one of the forty two feature films he directed, silent and sound, extant and lost, written by fourteen international scholars and the editors, commissioned and published to coincide with the Pordenone showings. Like the festival itself, it was only possible through the dedicated work of many other people, most obviously the organisers of the festival and film staff at the Library of Congress and other archives who made suitable for high standard screening with accompanying music several films considered wholly lost, as indeed nearly all of Stahl’s silent films were till recently. The book was put out with remarkable speed, little more than two years from inception to publication, a feat which owed much to its publisher John Libbey’s ability to work to a time scale and largesse with illustrations university presses could not match.

The book was first and foremost an introduction to and analytical study of Stahl’s oeuvre, an attempt to present his nearly forty years of film making to audiences less aware than they should be of a major figure in both silent and sound American cinema, half hidden through a concatenation of circumstances – in particular the supposed almost complete disappearance of the silent oeuvre; the timing of his death at a point before critical interest in Hollywood’s veterans, his peers who mostly outlived him, as displayed in Charles Barr’s illuminating table in the introduction to our book, moved them, but not him, into critical focus; and as well the unsolved mystery of how and why nothing of his correspondence and memorabilia survived his death.

So, mysteries to vex biographers at the end of Stahl’s life, and many mysteries at the beginning. Our book was not a Stahl biography, a task that still awaits an intrepid film historian, but biographical factors could not be ignored, though the combination of extreme pressures of time and lack of expert genealogical skills meant that I – responsible for research into Stahl’s early years – could in this area do little other than summarize what was known at the time of writing, adding only minor elements from my time-impeded research. The result was that, however much the book revealed about the texts and contexts of his films, in two areas we had to admit failure. (1) Stahl’s family origins, his parents, possible siblings, birthplace, emigration to America, arrival and early life in New York; and (2) Stahl’s theatrical career and entry into film acting and film making before he became a subject of newspaper and trade magazine interest with his first credited directions from 1918. (2) is a question for another time and other researchers, and perhaps even more difficult than uncovering his family origins because involving probably immitigably lost records rather than extant consultable ones such as federal and state censuses. Here our book, through Richard Koszarski’s intricate research on the uncredited Lincoln Cycle (1918), its episodes shown to great applause over the days of the festival, and our own recovery of material on what was almost certainly Stahl’s first feature, the lost A Boy and the Law (1913), also uncredited, helped advance knowledge of the pre -1918 years. But there were few other discoveries compared with the mass of material uncovered from 1918 on – the finding of one provincial stage appearance in 1909, two years before his 1911 Broadway appearance in Speed, for instance – is helpful but hardly a major breakthrough.

As for (1): after our book was published an amateur Greek genealogist, Giannis Daropoulos, whose area of special interest is the origins of East European immigrants to the United States who entered the movie industry, contacted us, offering us the wealth of material about Stahl’s origins that he had recently uncovered through patient and skilled examination of public records. Of course, regretting that we had not known him while working on the book, we gratefully accepted his offer, suggesting joint authorship of a piece on his revelations about Stahl’s beginnings. He modestly declined, offering us his material to use as we wished. Our reply was that we would gratefully use it, with his continued guidance, but would leave readers in no doubt whatsoever that the material, for which film historians and future biographers would be indebted, came from his researches.

In what is set out below, it must be recognised that information found in old censuses, naturalisation, birth, marriage, and death records, etc., can be far from straightforward, often requiring interpretation and the exercise of imagination. On the one hand, the subject may have misremembered (obviously a common occurrence), or fabricated (as Stahl did, for instance, when he entered his claim to have been born in New York into the 1940 census ); on the other, an enumerator or other official may have misunderstood or mis-transcribed statements, something especially likely with immigrants without, or with little, English, questioned by inexperienced officials. For instance, Stahl’s ‘Declaration of Intent’ naturalisation document of 1918 contains a flagrant error committed by an official who in the section requiring a statement forswearing other national allegiances stamped in the name of George V. Does this tell us that Stahl’s family stayed in England on their way to New York, thus opening up new, wholly unexpected areas of research? The answer is No; the official made a simple error with the wrong stamp. Further, a name like Strelitzsky / Streletzsky was particularly prone to different and confusing spellings as seen below, and both Stahl’s parents’ Jewish forenames had prolific variants. ( Strelitzsky is the form that we use throughout except where transcribing variant forms from documents, for the forenames, see below). For instance, an inexperienced reader of censuses, in looking for the Strelitzsky family in the 1900 Federal Census, would be likely to pass over the name Triletzky, when in fact it must be an enumerator’s misunderstanding and mis-transcribing of an unfamiliar name.

We have organised the updated information as it exists now, expanded by Giannis Daropoulos’s many discoveries, eight months after the publication of our book, into seven categories:

1. John Stahl’s birth place.

2. John Stahl’s birth name.

3. John Stahl’s parents.

4. John Stahl’s brother.

5. John Stahl’s emigration to the US.

6. The Strelitzsky Family in New York in the early 1900s.

7. John Stahl’s Marriages.

1. JOHN STAHL’S BIRTH DATE

The first problem is Stahl’s birth date. This is usually given as 21 January 1886, the date on his World War II draft card (1942), noted in the book by the editors. This is the date regularly given in studio publicity both prior to and after 1942, though accompanied by the born in New York fiction that Stahl stuck to throughout his public life. The Russian originals that might prove or disprove this date are unknown. (Would they have survived World War II ?) We accepted this date as uncontentious, but in fact there are other years with a claim. Stahl’s 1918 World War I draft card states 1884. In the book I suggested a scribal error, such as were common when statements were taken by an official. However, this date is also repeated in Stahl’s naturalisation ‘Declaration of Intent’ of 25 September 1918. It is quite possible that this year is correct and, if so, that Stahl may have had a reason for choosing the later 1886 date over it as part of his public image – the obvious one being a wish to present himself as younger than he was, which in the theatrical and film worlds, as in many others, might well have been advantageous. The issue is further complicated by the date of 1883 on his marriage record of 1906. While there is no indubitable reason for preferring one of the earlier dates over 1886, a couple of added years maturing might be thought to make more likely Stahl’s claim that he began his theatrical career in 1901-2, since he would have been seventeen rather than the fifteen he claimed. However, though he named the debut play Du Barry starring Mrs Leslie Carter, the story is as likely to be romantic fantasy as truth. Our conclusion is that the birth date question cannot be completely resolved between 1884 and 1886.

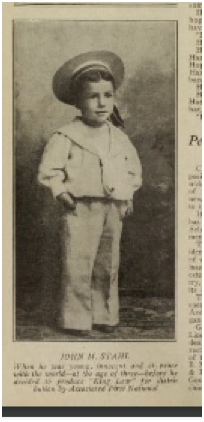

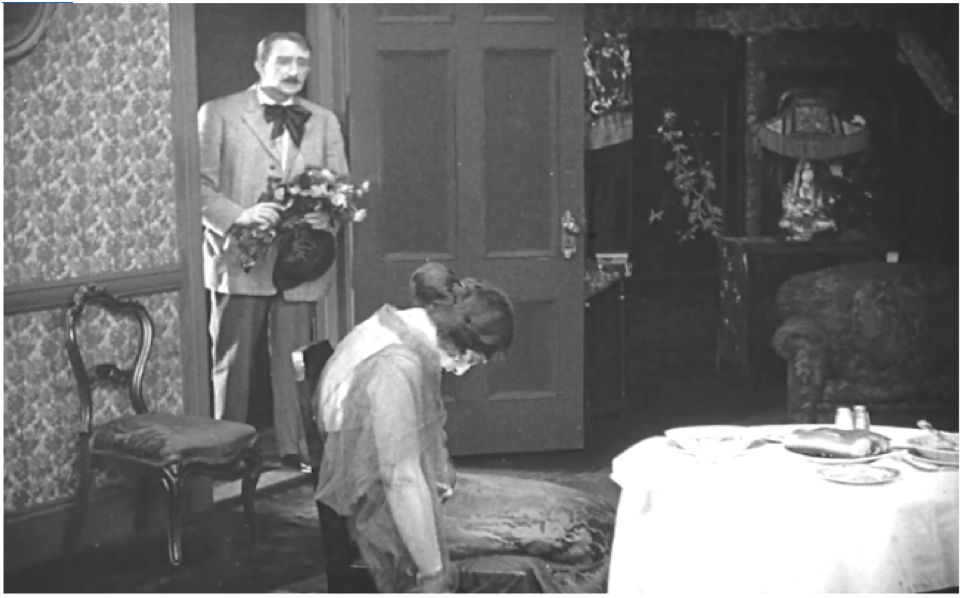

[Real or more likely a Joke? The caption reads: ‘JOHN M. STAHL When he was young, innocent and at peace with the world – at the age of three – before he decided to produce “King Lear” ‘ – a reference to an early plan for a Shakespeare film with a surprisingly enthusiastic producer in Louis B. Mayer. Moving Picture World, 21 May 1921, 284]

2. JOHN STAHL’S BIRTH NAME

In the book we repeated information available since 1950, but little known until recently, that John Malcolm Stahl was not the director’s birth name, and that he was born Jacob Moritz Strelitzsky (or variant spellings of the same, e.g, Jacob Morris Strelitzky / Streletzski / Strelacki, etc). This information, as related in Joe Adamson’s chapter, ‘The Case Against John M. Stahl’ in the 1999 John M Stahl San Sebastian volume, was first published as a result of the legal challenge to Stahl’s will brought by his daughter, Mrs Sarah Appel (by his first wife Minnie Goldberg, later Cooper), in which she announced the information of Stahl’s Russian birth, original name and the claim – as yet unverifiable that as a young man he had served prison time in New York and Philadelphia – as part of her accusation that Stahl’s third wife, Roxana, had blackmailed him into leaving his estate to Roxana and only money in his bank accounts to her, by threatening to divulge this information. As described in our book the case never came to court. Though the accusation of blackmail seems unlikely, and the claim of a criminal record under aliases, which she named, remains unproven, though possible and interesting in relation to the narrative of A Boy and The Law, the Russian birth is verified in many places and there is absolutely no reason to doubt the specific birth name, which is present in various censuses and other documents, and was of course known to Sarah’s mother, Minnie, and through her to her daughter.

3. JOHN STAHL’S BIRTH PLACE

Stahl claimed publicly throughout his mature life that he was born in New York City, an invention most plausibly viewed as an ambitious young Jewish Russian immigrant’s fast track americanising of himself. Aged seven or nine when he reached New York, the Russian and Yiddish speaker was young enough to learn English without the accent that would have marked him as an immigrant. His claim to be a New Yorker rather than an escapee from an obscure shtetl is understandable, but why didn’t he abandon the deceit once it had served its purpose and he was an established film maker, especially when fellow Jewish immigrants such as Louis B. Mayer must have known or guessed his origins? Perhaps the embarrassment of publicly admitting the deceit made him hang on to the fiction. Another factor may have been that, unlike his brother, he was probably, like his parents, never naturalised, remaining an alien; the ‘Declaration of Intent’ to be naturalised which he made in1918 may never have been followed by the necessary second part of the naturalisation process, the ‘Petition for Naturalisation’.

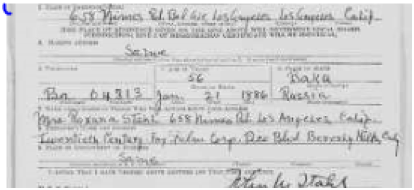

Los Angeles address, an 1886 birth date and Baku, Russia as birth place.

On his 1930 census form Stahl puts na (not applicable) to the year of naturalisation query, which seems to settle the question. His failing to take the second step is difficult to rationalise, but, whatever the reason, would have left him with a motive for continuing his claim that he was born in New York, though in official documents he told the truth about being born in Russia, probably worried about sanctions for giving false information, with only one exception, the 1940 Federal Census ( possibly answered in his wife, Roxana’s, presence – see below). The 1905 New York census, though listing him as born in Russia, also lists him as naturalised, either an enumerator’s error or the young Stahl’s deliberate invention. If the latter, it is readable as his early experimenting with self – metamorphosis. But of course these documents were not seen by his peers. Only in 1950, after his death, when Los Angeles newspapers printed the story of his daughter Sarah Appel’s challenge to his will were his Russian origins made public, though almost totally ignored.

Stahl’s WWII draft card with his very prestigious Los Angeles address, an 1886 birth date and Baku, Russia as birth place.

It is now generally accepted that Stahl was born in Baku, then part of Russia, now part of Azerbaijan (see map below). Evidence for this is his statement in his WWII draft card (1942) which adds Baku to the Russia of the WWI card (1917-18); his ‘Declaration of Intent’ to be naturalised (1918) that says he was born in “Becau” (presumably that hastily scrawled document’s version of Baku); his brother Alexander’s death certificate which states “Bakou”, Russia as his birthplace, repeated in Alexander’s daughter Molly’s (Stahl’s niece) death certificate. Baku was, it has to be said, not the most obvious place for the Strelitzsky family, with their probably Polish derived surname, to live, and one wonders through what historical circumstances the parents came to be there, possibly through expulsion of Jews from the Pale of Settlement, or drawn by the results of the early nineteenth century oil boom. But it is very difficult to ignore the evidence of both brothers’ statements of their birth place. Stahl certainly falsified some aspects of his early life, but there seems no conceivable reason for both brothers to invent a false birth place. In the 1920 federal census, their mother, “Ida” ( age given as sixty seven, but certainly at least seventy), gave the birthplace of her father, mother and herself as a place in Russia that, apart from certainly beginning with an L, is illegible, and unclarified by the Ancestry site, which we guess as Lida / Leeda in Belarus. Of course, this, if reliable, does not contradict Baku as the brothers’ birthplace, since Ida may have met and married Ary, who was certainly born in Suwalki, in Suwalki or nearby and moved with him to Baku where the brothers were born.

Present day Baku on the edge of the Caspian Sea in Azerbaijan extremely distant from Western Russia and Hamburg far off the map to the West.

3. JOHN STAHL’S PARENTS

In The Call of the Heart I noted that I could find no record in newspapers, trades or publicity of Stahl ever mentioning his mother, or any sibling, and only two fleeting contradictory references to his father as a merchant and as a civil engineer. Since then Giannis Daropolous, along with many other things, has discovered the identity of all three, father, mother and older brother.

Stahl’s father was Aryeh or Aaron Strelitzsky – the first forename the one that appears in Hebrew characters on the tombstone seen below, the second in different forms in official documents (Aaron or Aron), with Ari or Ary and in one instance the americanised Harry, diminutives of either Aryeh or Aaron, appearing in other documents. (Ary is the English inscription on his gravestone). It has been suggested to us by Lori Motola Hoffman, an expert in Jewish names and grave stone inscriptions, that it is possible that the sons, when they came to commission his monument, might not have known what Ari’s formal name was and left it to a rabbi to decide. What is beyond doubt is that this plurality of names refers to the same individual.

The Stahl Brothers’ father, Arye. Photograph kindly given by Alexander’s great granddaughter, Ellen Bacon

Stahl’s father was born circa 1845, almost certainly like his sister, in Suwalki, a Polish part of the Russian empire, which explains the Polish origin of the family name and also the family’s return from Baku to Suwalki before leaving for Hamburg and New York. His occupation was “laborer”, according to the passenger list for the SS Moravia on which the family sailed from Hamburg to New York in 1893, with the German list noting him as a “zigarettenarbeiter”, a cigarette or cigar factory worker. In the 1900 federal census his occupation is stated as “tailor”. In the 1910 census it is “ladies waist operator”. His death certificate (17 December 1912) lists him as sixty eight and an “operator”. As an uneducated, non English speaking immigrant he would have undertaken various jobs, the pattern above suggesting that he mostly worked in the clothing industry centred in the Lower East Side where the family lived. Though evidence is so scarce that any further statements about him would be wholly speculative, the one thing that can indubitably be said of him (and his wife ) is that, like so many other Russian immigrants, suffering from anti – Jewish legislation and fear of pogroms, he was determined to escape to another life in America, saving with difficulty money for the steerage fares to New York and travel through Russia before reaching Hamburg.

Stahl’s mother was Hodel Strelitzsky (the Hebrew name on the gravestone, with Adella [sic] the English inscription), known also in various records as Adela, Adele, Eidel , Edde, and Ida, once aberrantly listed as Teide). Born circa 1848, she outlived her husband, dying in Brooklyn on 20 February, 1925. Neither she nor her husband ever became naturalised. Their grave in Mount Moriah Cemetery, Fairview, Bergen County, New Jersey, which has “Streletsky” as the family name, has Hebrew characters which have been kindly translated by and expertly commented on by Lori Motola Hoffman. The text the brothers chose for it is conventional, “Here lies our dear father, our teacher the mentor Aryeh, son of Reb Abba”. And for Hodel “Here lies our dear mother Mrs Hodel, daughter of Reb Yehoshua Binyamin.” (Reb is an honorific not to be confused with Rabbi).

Stahl’s parents’ grave with Hebrew and English inscriptions

4. JOHN STAHL’S BROTHER

In the biographical part of The Call of the Heart I speculated on the likelihood of Stahl having siblings, but, as with Stahl’s parents, had to abandon searching for lack of time, evidence and expertise. But Giannis Daropoulos, having traced Stahl’s parents, then identified Stahl’s only sibling, his older brother, Alexander Strelitzsky (later Stahl), born, according to his naturalization petition (1901), on 21 July 1876, a date confirmed in the 1900 census and his obituaries in Los Angeles and San Francisco newspapers. (That both brothers were born on the 21st is an oddity which no doubt one should just accept as an oddity). But there are the expected variations – 1875 in his WWI draft card, the 1910 census, and his gravestone; 1877 in the passenger lists of the SS Moravia, and in the 1920 and 1930 censuses. In his social security index 21 July 1878 is the given birth date. 1881 on his death certificate, a document which contains another major error, is certainly too late. It also lists his birthplace, as “Bakou”, Russia, which is an important confirmation of Baku as the Strelitzkys’ home, despite their connections with Suwalki.

Alexander seems to have been, like his brother’s, an adopted name, in his case perhaps consciously binding his Russian past to an American future, while John’s chosen forenames (John Malcolm, not Jacob, which would have functioned biculturally like Alexander) looked only to the American future. Alexander’s original name seems to have been either Benjamin or Solomon, both of which appear in early documents – Benjamin in the SS Moravia passenger lists and Solomon in the 1900 census. The appearance of two very different names for the future Alexander is odd, but we should remember that early records are full of anomalies. Besides, it is quite possible that he possessed and used both forenames. Alexander Stahl (Stahl since 1906, just before his brother took the name, inevitably suggesting close fraternal consultation about the change), a retired “merchant” in his Los Angeles Examiner obituary, was involved in mineral water dealing at the time of his naturalisation in 1901, was a lamp factory salesman in the 1910 census, in the 1920 census was listed as the proprietor of a stationery store, and in the 1930 census as retired. He does not seem to have been very well off, certainly not compared with John, because the 1930 Census records his domicile as rented at $83 per month. Sometime in the 1930s he moved to Los Angeles with his second wife, Clara Sackheim Stahl and their four children, with William, the oldest, by his first wife, Rose, who died young, staying in New York. Alexander died, like John of a heart attack, in Los Angeles in 1939. Giannis Daropoulos’s research enabled newspaper searchings which found press reports of his death in the Los Angeles Times (13 Feb 1939, 21) and the San Francisco Examiner (14 Feb 1939, 3), the former beginning “Film Producer’s Brother Dies….Alexander Stahl to be Buried Tomorrow” and continuing:

“Alexander Stahl, 63 year old retired merchant and brother of John Stahl, producer at Universal Studios, died early yesterday in his home at 6118 Lindenhurst Ave from a heart attack. He leaves in addition to his brother, his widow, Mrs Clara Stahl, three sons, Dr William Stahl of New York City, Aaron and Leo Stahl of Los Angeles, and a daughter, Nita Stahl….”

The obituarists’ knowledge of Alexander’s relation to John suggests that it was well known

and makes it likely that the brothers were in contact (as they must have been over the deaths of the parents and the memorial to “our” parents that they commissioned), and that Alexander may well have moved to Los Angeles in order to be near his brother. Like John, Alexander seems to have given up the religious practices he was born into. His gravestone is very plain with just his name, dates and the word “Father”, and above those a Masonic sign. He is buried in the Forever Hollywood cemetery.

Alexander Stahl in 1938, photo kindly given by his great granddaughter Ellen Bacon.

5. JOHN STAHL’S EMIGRATION TO NEW YORK

It is certain that the Strelitzsky family emigrated to New York City from Hamburg in 1893, on the SS Moravia (Hamburg America Line), arriving in New York on 10 April 1893. They are listed in both the American and German passenger lists.

The US passenger list has Aron (age 48) and his wife Eddel Strelitzki (age 46) and two sons, Benj. (age 16) and Jacob (4), with Aron’s occupation given as “laborer” (far from the civil engineer Stahl claimed in the late 30s). There are some oddities, particularly the age of Jacob, but mistakes in recording the age of young children are understandable. Benjamin (Binyamin) was probably Alexander Stahl’s original name or one of two. In the passenger list in the middle of a long sequence of “Russian” entries for native country, “Polland”[sic] suddenly appears alongside Aron Strelitzki. The combination of the name Strelitzki’s Polish associations and ‘Suwalk’ (i.e. Suwalki, a Polish part of the Russian Empire) being listed as the family’s place of last residence before sailing to New York via Hamburg may have led to the assumption that the family was Polish.

The German Passenger List (in German) parallels the US list, though giving Jacob’s age as seven, and his father’s occupation as “zigarrenarbeiter” (cigarette worker). Native country is not noted on this form but “Suwalk” is as “previous place of residence”.

While we have no doubt that these Strelitzkis are young John Stahl’s family, there are questions as to how from Baku in the extreme south east of Russia they came to be in Suwalki, before sailing to Hamburg. Given Ary, their father’s, birth in Suwalki and the probability that he married Ada there, the brothers’ births in Baku could mean that the parents as Ashkenazi Jews were expelled to Baku, which had a Jewish population of 10,000 by 1884/1886 ( John’s birthdate, Alexander’s being circa 1876). Or perhaps the city’s growing industries, particularly those related to the Baku oil boom, attracted the parents. Later, when the family moved westwards to their eventual destination of Hamburg with its Hamburg America Line ships sailing to New York, the last phase of their journey is traceable. After Suwalki, where there were relatives, they seem to have reached Libau (present day Liepaja in Western Latvia), with its substantial Jewish population and access to Hamburg. This route – Suwalki – Libau – Hamburg – seems to be confirmed by the evidence of public records (Suwalki in the ships’ passenger lists, Libau in Stahl’s naturalisation ‘Declaration of Intent’).

Suwalki, with which Stahl’s parents had family bonds, marked on a map which gives an idea of the last stages of the family’s journey to Hamburg.

Not the SS Moravia, but a similar ship of the Hamburg America fleet .

6.THE STRELITZSKY FAMILY IN NEW YORK IN THE EARLY 1900s.

Between 1893 and 1900 there is no information about the family, whose experience of immigrant New York must have been like the struggles of so many other immigrants, with poor parents and eventually higher achieving children. In the 1900 census below, both parents are listed as unable to read, write or speak English, while with the sons, yes is noted for all three categories. In the 1930 census Alexander says that he never attended school; whether this is literally true or the boast of a Self-made man, is a difficult question; but John stated in the 1940 census that he attended until high school 4th year. But attendance until eighteen is exceedingly unlikely; some attendance at elementary school and perhaps a little beyond is altogether more convincing. (This 1940 census form is the only official document in which he claimed he was born in New York, as well as having the latest birth date “about 1888”, he ever gave). Giannis Daropoulos has suggested that the presence of Roxana at the interview led him to distort the truth in a number of ways, and that she might have believed he was born in New York, was a couple to four years younger than his real age, and more formally educated than he actually was. Whatever schooling he had, is likely to have been sporadic because, as with many other immigrant children, work supporting the family came first, as one can see from the listing of his occupation, rather than being described as a student, in the 1900 census. But he must have been a gifted child who picked up things quicker than most.

Canal Street and Allen Street are easily seen on this map of the Lower East Side

The first glimpse that we have of the Strelitzsky family in New York is seven years after their arrival, in the 1900 federal census, which lists, under the surname Triletzky, Aron (52), Ida (48),and two boys, Jacob (16) and Solomon (24), living at either 51 or 53 Canal Street, in Lower East Side Manhattan, an area near to Little Italy and Chinatown, densely Jewish at the time and the centre of the garment industry in which there are indications that Ary worked as well as the the sons for a while. There are oddities here but they seem explicable. Triletzky for Striletzsky or Strelitzsky is a plausible mistake for an enumerator (in this case one Patrick Masterson ) likely to be unfamiliar with East European names. Solomon for Benjamin has the likely explanation given above in the section on Alexander. Solomon’s (Alexander’s) occupation is described puzzlingly as a “secler puser”, which may be a redundant doubling of the Yiddish for purse maker with pu[r]ser for purse maker. Yiddish was certainly the home language of the family. Aron’s occupation is given as “tailor”, and Jacob is listed as aged sixteen (which accords with the 1884 birth date) and his occupation is listed as “salesman”. All these are plausible but we should remember that occupations were probably temporary and subject to change.

The next glimpses are of older brother Alexander submitting his application for naturalisation (19/6/1901), his address 57 Canal Street, the same street as that of the family in the 1900 census, and his occupation mineral water dealer, then marrying Rose Novgorod in the same year or early 1902, with the birth of a son, William, in December 1902. In the 1905 census, with Alexander married and living elsewhere, the family were now living at 33 Allen Street adjacent to Canal Street, with Jacob, now 21, signed in familiarly as Jake, occupation “trunk maker”. There is an obvious error, noted above, where he is listed as a citizen rather than as an alien. Stahl claimed that he began his theatrical career either at the end of 1901 or beginning of 1902, taking a role – obviously as a supernumerary – in Mrs Leslie Carter’s performance of Du Barry (on Broadway, December 1901- May 1902). If this is true rather than the romantic story it might be, it may be felt that the 1884 birth date makes it more likely by giving Stahl two extra years to mature before first treading the boards. His occupation as trunk maker need not invalidate this since, whether in 1901-2 or later, Stahl’s theatrical beginnings are likely to have been precarious, with more mundane work to fall back on. But it must be emphasised that, apart from Stahl’s claim, there is no evidence as to when exactly his theatrical career began.

1906 was an important year for the sons, with Jacob marrying Minnie Goldberg, a fellow Russian Jewish immigrant, and Rose Stahl, Alexander’s wife and mother of a son, William, dying. Likewise 1907, with the birth of Stahl’s daughter, Sarah, and Alexander’s marriage in New Jersey to Clara Sackheim. In the 1910 federal census the parents were living at 243 Norfolk Street, quite close to the Canal and Allen Street addresses, listed as not speaking English, but Yiddish. At this time Alexander was living with Clara and three children in Brooklyn, working as a salesman. John does not appear in the 1910 and 1915 censuses, as noted below in the section on Minnie Stahl. By 1910 he must have been well into his acting career, so that he was probably away with some stock company, as he was in September 1909 in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in a play called Cradled in the Deep, as noted in The Call of the Heart. In September 1911 he had a part in a Broadway play, Speed, directed by a pre-filmic Cecil B. De Mille in which Sydney Greenstreet acted. In 1912 Ary died, widowing Ida. By 1915 there is evidence (below, in the section on Stahl’s marriages) that John’s marriage with Minnie was over and that the couple had divorced, though a divorce document has not been found. In 1918 Stahl married Frances Irene Reels, an actress turned screen writer who would write either the story or scenario for five of his films beginning with Her Code of Honor (1919). In 1918, on the evidence of his ‘Declaration of Intent’, John and Irene were living at 224 West 46th Street. In the 1920 census, Ida, eight years widowed, her surname written down as “Stretisky”, was living in Moore Street in Brooklyn.

As we set out in in The Call of the Heart, there are extremely large gaps in our knowledge of Stahl’s activities up until 1917-1918, particularly as regards his progression towards the point where, in his ‘Declaration of Intention’ (to become naturalised) in 1918, his path is certain enough for him to list his occupation as “motion picture director”. And a century later, this remains so, a major problem for a future biographer. His early theatrical career has up till now yielded only two sightings – a Pennsylvania stock company appearance in 1909 (small yield for much research!) and Speed in September 1911. Although he was a first language Yiddish speaker, we could find no evidence that, as some have imagined, he worked in New York’s Yiddish theatre. Bosley Crowther’s assertion in his biography of Louis B. Mayer that he was a well known director in it was presented wholly without evidence. Stahl’s move into film, no doubt through acting is even less evidenced. Not a single film role has been identified, though most, even all of the films may be lost. One is left with an imagined scenario, where, although the status of the actors varies hugely, one can see him like an earlier Clint Eastwood keenly observing and learning from his actor’s position how films were made, thinking of future possibilities.

In The Call of the Heart we were as certain as we could be that the lost 1913 film A Boy and the Law, the direction of which was claimed by Stahl, was indeed his, and indeed his granddaughter, Joan Lester, has related to me that he talked about it as his first film. And Richard Koszarski’s chapter on The Lincoln Cycle ( published at greater length in the journal Film History) makes absolute the crediting of those eight surviving short films of the cycle– which were so well received at Pordenone – to his direction. Both films being the projects of highly self-promoting figures (Benjamin Chapin and Judge Willis Brown) averse to crediting others on their projects, Stahl had to assert credit himself. In the piece in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle ( 7 June 1917, 22) in which Stahl claimed the direction of The Lincoln Cycle, he advertised his direction of a seven reel picture, Love Thy Neighbor, but this film, if made, has disappeared without trace. Clearly there is much searching still to be done.

7. JOHN M. STAHL’S MARRIAGES

(i) Stahl’s first wife, Minnie Goldberg, and daughter, Sarah Stahl (later Appel)

Stahl’s first wife was Minnie Goldberg, born in the Kovno region of Russia in either 1885 or 1887. The marriage took place in New York on 7 July 1906, between “Jacob Stralecki” listed as age 23 and “Minie” [sic] age 21. In that the Strelitzskys lived on Canal Street and she lived on the adjacent Allen Street, she, a Russian Jew like Jacob, was almost literally the girl next door. A daughter, Sarah, was born on 21 July 1907. In the birth certificate Jacob Stralecki has become John Stahl, which, with the addition of the second name Malcolm (usually just the initial M), will be his name for the rest of his life. The marriage did not last, though no record of the divorce has yet been found. Giannis Daropoulos’ s intricate research discovered some indications of the marriage’s decline. In the 1910 federal census, Minnie ( four years older than the twenty three listed, her status marked as married) and Sarah are living with her parents in Brooklyn, without John. His absence is very likely explained by his pursuit of his acting career. In the 1915 New York census she is still living with her parents, again without John. There is no recording of her marital status, but she, as well as her father, is labelled a head of household (i.e. mother and daughter), indicating that John no longer has that position. This tells us that the marriage was dissolved some time between the 1910 and 1915 censuses.

Minnie Goldberg, photo kindly contributed by Stahl’s granddaughter, Joan Lester.

Minnie Goldberg was wholly absent from earlier accounts of Stahl’s biography. She first appeared by implication when Stahl’s daughter Mrs Sarah Appel (Appel by her marriage to Sidney Appel in Chicago in December 1931, and now in her forties) challenged her father’s will, which left all his considerable estate to Roxana and only money in his New York bank accounts to Sarah, claiming that Roxana had blackmailed Stahl over the will by threatening to reveal his Russian origin and that as a young man he had a criminal record under aliases in New York and Philadelphia. Reported in Los Angeles papers in January 1950, this appearance of Stahl’s also previously unknown daughter meant the existence of an unidentified mother. An essay in the 1999 San Sebastian volume (“The Case Against John Stahl” by Joe Adamson) was the first to catch up with these events, but without identifying Minnie. Our research into the Santa Monica court records (cited in our book) managed to find reference to her in letters from two New York doctors that Sarah used to delay the deposition necessary for proceeding with the case. The letters specified that Minnie Cooper, living in New Rochelle, was seriously ill with a very severe disease. Probably because of looking after her mother, and, one might think, a realisation that her claims of Roxana blackmailing Stahl over his past were unlikely to be believed, Sarah never filed her deposition and the case went no further, though she was later awarded a small $30,000 share of the half million dollar estate. Minnie’s surname, Cooper, as we guessed, was the name of a later husband who turned out to be Isidore Cooper whom she married in 1919. We have found no evidence of when Minnie died, but, given the gravity of the doctors’ description of her illness in 1950, she is unlikely to have lived far into the decade. Sarah lived until February 1990, her daughter Joan Lester (Stahl’s granddaughter), is an important recent contact interviewed on this website about her memories of her grandfather.

(ii) Stahl’s Second Wife Frances Irene Reels

Photo of Irene Reels aged seventeen from the Winnipeg Tribune

In the book I followed a faulty lead from her Los Angeles Times obituary (11 November,1926, 14) – which stated that Stahl’s second marriage to Frances Irene Reels, credited as the story writer or scenarist on five of his early films, took place circa 1914, but the New Jersey marriage index shows that it actually took place in 1918 (State File number 31138; she under the name Irene Reels, and he as John M. Stahl, occupation “film producer”). Born in Smithville, Monroe County, Mississippi, 29 September, 1892, her family name was Reel, but she added the final ‘s’ to form her professional name, as did her mother. I conjectured that Stahl may have met Irene when she was acting in New York. ‘Find A Grave’ gives credence to this, saying she came to New York with her mother, also an actress, and their working together is confirmed by articles discovered by Giannis Daropoulos in the Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, 15 and 29 August, 1909, noting both coming from the Lyceum Theatre Stock of Minneapolis to appear in a play called Men and Women. There is also the serendipitously discovered photo of her above from The Winnipeg Tribune (27 November, 1909) on tour in Canada as a seventeen year old actress, costumed as a cowgirl, nine years before she married Stahl.

Irene, after becoming a major partner in Stahl’s early 1920s filmmaking, died suddenly and unexpectedly after a minor operation towards the end of 1926. For a screenwriter of repute, picked out for praise in numerous reviews of Stahl’s films, and said in her Los Angeles Times obituary to be widely known in Hollywood social circles, traces of her have proved difficult to find. The Los Angeles Times (16 March 1923, 31) reported that a novel by her called Poor Men’s Daughters had been bought by Mayer for filming. The film seems not to have been made and the novel has not been traced; the probability is that it was unpublished. As for photos, the fuzzy picture of “that clever little ingenue” (as The Winnipeg Tribune called her), nine years before she married Stahl, is the only one yet found.

(iii) Stahl’s Third Wife, Roxana McGowan

Stahl married his third wife Roxana in 1931 in Chicago. Born Roxana McGowan in 1897, she had a short film acting career in the Mack Sennett troupe, married the film director Al Ray and had two children with him, who became Stahl’s stepchildren, C. Ray Stahl and Roxana Ray Stahl. She was well known on the Hollywood social scene, e.g. the detailed description of her gown when attending the premiere of Marie Antoinette (Petaluma Argus-Courier, Calif, 25 July 1938). See also the note in our book in the chapter on O, You Beautiful Doll on her hosting an occasion in honour of the Swiss conductor Charles Műnch.

Roxana during her short film career

After Stahl’s death she remarried with Horatio B. (“Ben”) Smith, a businessman who died in 1964. She died aged 79 on 22 November 1976 in Santa Monica. In the absence of other evidence it seems likely that she was responsible for the disappearance of Stahl’s personal records either on her own initiative or at Stahl’s request. As is obvious, the disappearance of this material has caused major problems for writers on Stahl, and has been a considerable factor in his neglect in the later twentieth century and the beginning of the twenty first. Though Roxana can be found occasionally pictured in Californian newspapers, in spite of this and the overtness of her interests in fashion, social life, and music, she remains an opaque personality, and the question persists how much did she actually know about Stahl’s early life? His census declaration in 1940, probably in her presence, stated that he was born in New York and claimed an unlikely full high school education; this may suggest that she believed he was born in New York, and her total denial of the truth of all the details of Sarah Appel’s initial challenge to Stahl’s will “generally and specifically each and every statement” (in the Santa Monica court archives, see The Call of the Heart, p.16), including his unarguably Russian birth, suggests that she could possibly have been unaware of his background. Here, though, we are in the realm of speculation.

By 1919, making films with direction credited to him on the East Coast before moving to Hollywood, Stahl, now aged either 31 or 33, exhibits a mastery of design and gesture in Her Code of Honor.