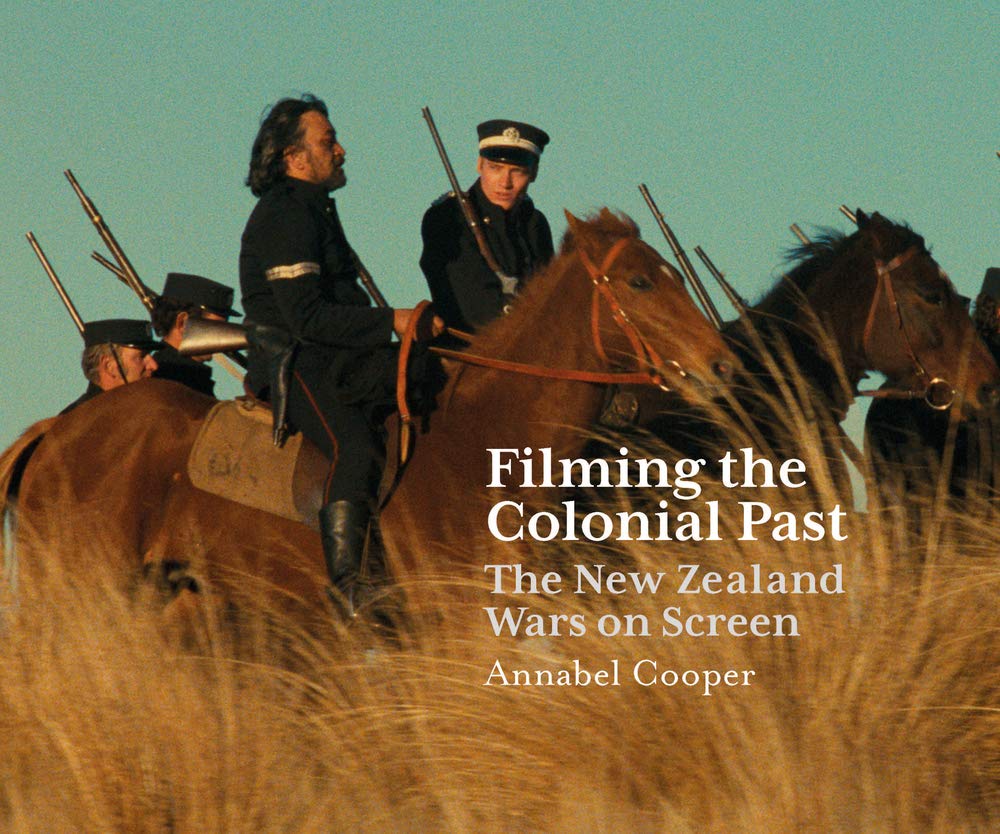

Filming the Colonial Past: The New Zealand Wars On Screen by Annabel Cooper – Book Review

REVIEW OF FILMING THE COLONIAL PAST: THE NEW ZEALAND WARS ON SCREEN by ANNABEL COOPER, Otago University Press, Dunedin, 2018

In Annabel Cooper’s work across fields that intermingle history, sociology, gender studies, literature, film and television, one of her most important roles has been playing a leading part in the increase in attention given by New Zealand scholars to that important figure James Cowan (1870-1943). Cowan, famously brought up on farmlands near the site of the Orakau siege commemorated in two of Rudall Hayward’s films, Maori-speaking, and with the foot in both Pakeha and Maori worlds that marks the central “cross-over” figures of so many of the cinematic works (especially The Te Kooti Trail, Rewi’s Last Stand, Utu and River Queen) that Cooper deals with in her book, was the author of the great two volume history The New Zealand Wars (1922-1923), of popular works including The Adventures of Kimble Bent (1911), in which he recorded the exploits of the renegade soldier who lived precariously in Titokowaru’s wartime camp, as well as many other books aimed at a wide audience and much influential journalism. This work on one of the most extraordinary of all New Zealanders ( who surely should by now at the very least have been commemorated on a postage stamp), has led by an easily observable path into what is, if I may quote myself, as Cooper generously does, New Zealand film’s most resonant genre, the New Zealand Wars films, for Cowan’s The New Zealand Wars was a major source of Rudall Hayward’s three cinematic “epillions”, i.e. small scale epics of national origin. Additionally his ‘A Bush Court Martial’, later elaborated in Tales of the Maori Bush (1924), lies behind the extraordinary sequence that ends Geoff Murphy’s Utu, as his reporting of Kimble Bent’s explanation for Titokowaru’s mysteriously abandoning Tauranga-ika because of his liaison with another Chief’s wife, stands behind a crucial episode in Vincent Ward’s River Queen. Though Cowan belonged to his era of assimilative optimism, an ideology largely overtaken by history, there are elements in him, as his influence on film makers of three very different periods shows, that are permanently inspiring, not least his place as one of the most influential “cross-over”, boundary breaking figures between the Maori and Pakeha worlds, even in his official war history as interested in indigenous as settler accounts and sources.

James Cowan whose writing resonates in the New Zealand Wars genre from the 1920s to the present

Cooper’s Filming the Colonial Past:The New Zealand Wars on Screen, with screen used in its widest sense to include television and video art, is nothing if not comprehensive: two large chapters on the patriarch of New Zealand film makers, Rudall Hayward – one on the early only fragmentarily surviving version of Rewi’s Last Stand (1925), and what both the writer and I agree is his masterpiece, The Te Kooti Trail (1927), happily extant and intact, and the other on the unhappily truncated sound version of Rewi’s Last Stand (1940 ); a major chapter on Geoff Murphy’s Utu, another on Vincent Ward’s Rain of the Children, and another on River Queen. Pictures (director, Michael Black, produced by John O’Shea, 1981) has abbreviated coverage, understandably in one sense, since it is a film whose reputation has steadily declined from being thought in some quarters when released, strange though it seems, superior to Utu, to a very low present day ebb, though it raises some questions central to the book’s meditations on film and history noted below. Nearly half of the book, though, is devoted to television and video, most substantially discussion of The Governor (1977), that enormously important production in local television history (largely restricted to the two episodes available on NZ On Screen) and of James Belich’s documentary series The New Zealand Wars (1998),which stand out over others, but space is also given to The Killing of Kane (1971), Greenstone (1999), Von Tempsky’s Ghost (2002), Frontier of Dreams, and, foregrounded in the late chapter on Maori creative control, Tatarakahi (2012, The Prophets (2013), The Kingitanga (2016) and others. As this summary indicates, the book is too wide-ranging for a review to do other than cover its most essential aspects; the problem for this reviewer increased by the fact that though bits of Belich’s The New Zealand Wars and two episodes of The Governor can be viewed on NZ On Screen, many of the other programmes mentioned are only available in New Zealand archives, cutting them out of close discussion when one is writing a review from the UK. Also my knowledge inclines me to the filmic, so I will mainly concentrate on what Cooper writes about Hayward’s films, Murphy’s Utu and Ward’s River Queen, as well as on her weightily generalising introduction and conclusion, which go beyond the cinematic instances.

These lay out governing attitudes revisited, expanded and nuanced throughout the book. Briefly they are:

(i) That the “New Zealand Wars” film (Cooper, like Belich, for what seem good reasons, prefers that title to the older “Maori Wars” and the more recent “Land Wars”) encompasses over its more than 90 year history major interpretative variations on the historical template, an obvious point but the devil is in the detail, the how and why, which the writer pursues.

(ii) That the films’ changing perspectives embody particular instances of a continuing doubleness as later revisionist history and cultural politics work on the historical template. Again the point would not surprise any critic aware of historians’ and others’ meditations on the history film, but again the devil is in the writer’s command of detail; as for instance, to take a couple of examples, when she points to the implicit local affirmative meanings within the tragedies of the Great (1914-1918) War, of Pakeha and Maori fighting overseas side by side (though some Maori tribes refused conscription) playing optimistically into Hayward’s 1920s films; and, more obviously, half a century later, the echoes of the Bastion Point and other protests, including those at the Springbok tour, resonating in Utu along with deliberately anachronistic details of costume and language. Here, though, it is interesting that in slightly shortening rather than lengthening the film into the director’s cut restoration ofUtu Redux, Murphy said he removed some of these references, which now seemed to him outdated. Perhaps it was a mistake to do this.

(iii) Well versed, as one would expect her to be, not only in the work of Cowan, Sinclair, Belich, King, Binney and other New Zealand historians, but in the film-orientated writing of historians like Robert Rosenstone, Cooper’s defence of the historical film emphasises the emotional pull of filmed history, a quality seen as valuable rather than compromising through its “drawing viewers into the experience and the emotions of the past”. She notes acutely, by the way, that “Cowan’s writing …was frequently anecdotal and sensitive to place and scene, lending itself readily to film”. (Actually, apropos of this, the Alexander Turnbull Library contains some small, not very impressive, sketches of film scenarios by Cowan, seemingly influenced by Hayward, as Hayward was by his writing). She finds useful a statement made by non-historian Geoff Murphy, that the makers of Utu were not historians, but “were trying to create a creative space in which history could be commented on”, a formulation she clearly likes for the freedom it gives to mix the literal and imagined. All the films dealt with are potentially illuminated by this.

Regarding this, the O’Shea production Pictures (1981, directed by Michael Black) is a film that has sharply and probably irrecoverably dipped in reputation since the days when it was considered by some superior to Utu, a view that looks wholly untenable now. Given short shrift in this book, it does, however, raise interesting problematics around the questions raised by the intersection of history and fiction in the historical film generally, and the New Zealand Wars narrative in particular, questions Cooper recognises as complex. Is part of the problem with Pictures, which was accused of distorting history to offer comfort to liberal white audiences, its naming the actual Burton Brothers at its centre, and crediting them with anachronistic liberal race views and imagined actions, leading to critical displeasure, even outrage, at fiction trumping historical fact? Why does this raise greater critical ire than instances such as the wholly unlikely journeyings of the woman alone, Sarah, in River Queen, which are seen and approved in terms of utopic should be rather than actual historical is, excusing historic anachronism, when the should be rather than is of the filmic Burton Brothers is condemned. Partly, this may be a matter of critical alignment with ideologies of the moment, but also a matter of the “creative space” given by allusion rather than definition. As Cooper points out, commenting on a frame from River Queen that shows the kupapa Hone and Major Baine, “There are echoes of historical figures in these soldiers in River Queen (2005) – but nothing too precise. As leader of the kupapa, Hone (Mark Ruka) has the implacable determination of Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui. Both the dashing style of Gustavus von Tempsky and the ruthlessness of Thomas McDonnell are apparent in Major Baine (Anton Lesser)”. The “nothing too precise” is revealing, and very relevant to the occluded semi presences of Anne Evans and Caroline Perrett in the narrative. Would Pictures have aroused less criticism if it had called the Burtons, say, the Taylor Brothers? Cooper works her way round such questions skilfully, without offering easy answers.

(iv) That the historical film is seen as being “a risky endeavour” for the New Zealand cinema, not only because of the costs of the historical film with its masses and battles, but because its content is “the difficult emotional territory of colonial history”. But the latter, if difficult, also fascinates as our narrative of origins.

(v) That the “puha western” ( Murphy’s description of Utu), differs from the traditional American western, on which it was in part modelled, “Unlike the portrayal of native Americans in some early Hollywood westerns, there was never any question that Maori actors would play Maori characters”. This leads to the book’s complex examination of the historically inflected role of Maori in the cultural productions of the genre most fundamentally concerned with Pakeha-Maori relations.

Also running through the book are two further central issues around which much material is organised

(vi) the genre’s intertextuality; the way in which the later films rewrite earlier ones, which demands in the analyst, as in the makers, a deep familiarity with the films; (and one hardly doubts that the makers of the later films watched, as part of their preparation, the earlier ones). Thus the moment in Utu when Kura dives preciptously into the river to escape, echoes Takiri’s leap in the surviving footage of the 1925 Rewi’s Last Stand; and, in Utu again, the way in which expectation are reversed when the primary “cross over” figure becomes the complex kupapa Maori figure of Wiremu (played by Wi Kuki Kaa), the Maori capable of loving Pakeha taking centre stage from Hayward’s whites capable of loving Maori. Or in River Queen where the heroine becomes the central protagonist and the traditional intermarriage relationship (signifying cultural bonding) of these narratives reverses the white male/ brown female couple for the white female/brown male pairing.

(vi) The most striking element of Cooper’s book is the intense attention given to the local specificities of the inter-cultural (later bicultural) film making negotiations and processes behind the films. This pervasive feature most distinguishes it from other writing in the field, and contains much that will be unfamiliar to overseas viewers of the films, but also, in many particulars, to New Zealand audiences as well. For instance, she notes what might well strike many watchers of the early Hayward films, the high standard of acting of the Maori performers – something noted even earlier during Gaston Méliès’ epic film making expedition to the North Island in 1912, where, in particular, Mata Horomona was much praised by Méliès himself. As regards Hayward’s leading Maori players, Tina Hunt and Patiti Warbrick, Cooper explains that “they were from guiding families [i.e. who acted as professional guides for tourists of an earlier age] and were skilled and experienced cultural performers who had moved directly into film acting” (something also preceded by Méliès discovery of the Reverend F. Bennett’s troupe of “Mahoris”). A more intricate instance is the information given about the actress who played Erihapeti in The Te Kooti Trail, Mere(wakana) Kingi, found by Hayward in a teashop, in a homely Whakatane version of Hollywood’s soda fountain. As Cooper informs us “Merewakana is a transliteration of Mary Völkner, indicating that she was named after the missionary Carl Völkner, who was killed in 1865 by Kereopa Te Rau in the act that reignited the wars on the East Coast. According to her children, Mere Kingi had been educated at Völkner’s mission at Opotiki and would have been strongly opposed to Te Kooti: and there were no doubt others among the Ngati Awa involved in the film who shared her opinion”. The passage then goes on to note a tribal division in that a minority of Ngati Awa joined with Te Kooti and the fact that, in spite of Ngati Awa opposition to Te Kooti, many Ngati Awa in 1927 belonged to the Ringatu Church and many Whakatane Maori remembered Te Kooti positively because of this. A little further on, Cooper writes about the casting (in unrecorded circumstances) of the seventy year old non-English-speaking Tuhoe Chief, Te Pairiu Tuterangi, as Te Kooti, a choice with various interesting intersections with the film’s staging of the past, since as a twelve year old he had joined Te Kooti as a powder boy,and, famed for his memory,as Cooper relates, brought to the film an attention to authentic detail such as the flax bridle on Te Kooti’s horse. Some of what she writes here is interesting speculation (based on one unnamed source, and in other instances she picks a way between different sources), e.g. the possibility that he was present at the killing of Monika and may even have “contributed to the staging of this scene in the film”. Cooper, though, doesn’t speculate about whether he, as a staunch Ringatu Church adherent, might have contributed to the protests which forced Hayward to change elements of the film’s sceptical treatment of Te Kooti’s religious practices. Certainly Te Pairiu Tuterangi as Te Kooti is an impressive presence in The Te Kooti Trail though not highly developed as a character. These instances are easy to digest because attached to individual actors, a Maori girl playing a Maori woman in an interracial marriage, who was named after one of Te Kooti’s victims, and an elderly non English speaking Tuhoe Chief playing the leader he had served under in his boyhood. They also remind us how close in time to the wars – only half a century distant – Hayward’s 1920s films were, and the importance he attached to historical verisimilitude, somewhat exaggerated in his publicity, but nevertheless an important constituent of the films.

Beginning with Rudall Hayward’s failed negotiations with Princess Te Puea over the use of Waikato Maori, wanted by the director as part of his search for historical accuracy in the first Rewi’s Last Stand ( negotiations in which both sides were severely cashstrapped, and her demands greater than Hayward’s total budget), we are made aware of the delicate negotiations attending the making of all the later films as well. Most non-New Zealand viewers will almost certainly be unaware of the complexities of tribal distinctions, and the fact that the wars were not a simple matter of Maori against the Government, but a highly complex affair in which, for various reasons, probably more Maori from different tribes fought with the government in Maori on Maori action against tribal enemies than fought against it (see Ron Crosby’s Kupapa;The Bitter Legacy of Maori Alliances, 2015 , curiously not in Cooper’s for the most part unimpeachable bibliography). For instance, when Hayward employed as alternative actors for the defenders of the Orakau siege, Te Arawa kupapa who had served on the government side, he was enmeshed in tribal disputes stemming from the wars. Kupapa characters are prominent, even crucial in the films, with a shift in emphasis taking place over time – with the government-siding kupapa in earlier films seen as good Maori against mistaken Maori (mistaken rather than demonised, the New Zealand films always embodying less extrreme views than the early American Western), but in later works, e.g. Utu and River Queen, occupying a more central and complexly fissioned role, as with Wiremu (Wi Kuki Kaa) in the former and Wiremu (Cliff Curtis) in the latter. In fact as Utu’s narrative reaches its end,Wi Kuki Kaa’s character assumes a greater centrality than the Pakeha characters, though Cliff Curtis’s Wiremu seems underwritten, for all his intended significance, perhaps a casualty of the film’s difficult production.

Hayward’s difficult film-making negotiations mentioned above constitute an early instance of a recurring pattern. By the time of the big Vincent Ward international production, River Queen, more than seventy years later, the situation had evolved considerably, negotiation with local iwi was no longer haphazard but highly organised with agreements drawn up “that covered employment, creative contributions, cultural security and protection of the river and sensitive landscapes during filming”. River Queen’s makers’ problems were much fewer than Hayward’s; more dissent had been expected stemming from divisions in the wars among local tribal people, and because descendants on the tribal side had made recent protests against statues honouring kupapa fighting in the wars. Cooper quotes Ward, Alun Bollinger and Tainui Stevens on the cooperation of film makers and iwi and the mutual benefits ensuing, though – and it must be remembered that the shooting suffered from delays and monetary crises – after the film there was some less positive feeling among some Maori, as recorded in the ‘River Queen ehui Disussion Forum 2006’ which Cooper picks her way carefully around. One specific instance of the kind of local post-release criticism encountered was that the training of Maori characters in River Queen to speak with Whanganui characteristics (a fidelity that few outside the Whanganui region could have picked up on), resulted in a view that it was “surreal” to have a character based on Titokowaru played by a Te Arawa man (Temuera Morrison) speaking in Whanganui dialect. Thus even the earnest attempt to authenticate the character by his local speech patterns is viewed as not redeeming the actor’s alien descent. Seventy years after Hayward’s problems with the Princess, differing expectations and attitudes towards cinematic art are still a complicating factor. Apropos of this Cooper stresses the bicultural melding of Maori and Pakeha participants and views in the making of Utu, a paradigm for later productions.

The book is finely designed with many illustrations augmenting the arguments of the text, most of them well chosen frames from the films and tv productions rather than the odd publicity still with which writers often have to be content. For this Otago University Press is to be congratulated. Some of the splendid stills from The Te Kooti Trail have the original coloured tints, for instance the bush-green colouring when Gilbert Mair leads his Arawa contingent through the bush,and the purplish tint for the death scenes of Jules and Taranahi. Seeing such moments in their colour- heightened original state is a great pleasure, underlining something I feel deeply, the absolute duty Nga Taonga (the National Film and Sound Archive) has to make Hayward’s films (and those of the later great pioneer O’Shea as well) available in commercial digital form, widening the availability of these precious foundational films at present only able to be viewed in the archive and in rare occasional screenings. Another still, which I don’t recall seeing reproduced before, is a shot of Peka Makarani / Baker McLean craftily manipulating an airborne cross to an offscreen audience of Te Kooti’s followers, presumably visible in other shots from parts of a scene excised from the film along with the notorious subtitles referring to Te Kooti “resorting to fake miracles” and Peka as “torture master” and “stage manager of miracles” that Hayward was forced to remove from the film under pressure from Ringatu church elders. Even more than with The Te Kooti Trail, which happily survives intact, the stills from the surviving footage of the first Rewi’s Last Stand give life to the substantially lost production (only the first reel and fragments surviving). There are four stills: Takiri and Ken meeting on the river bank, Rewi Maniapoto and the chiefs debating whether to fight at the famous Orakau siege, a dramatic longshot of the cavalry charge at Orakau, and a striking action frame of Thomas MacDonnell duelling with taiaha in a friendly trial of strength with a sword-wielding Gustavus von Tempsky. ( The treatment of history in the New Zealand frontier films differs from the American in many respects, but in one is similar, that major historical figures recur in them, Custer, Wyatt Earp, Doc Holliday, Jesse James, Sitting Bull, Cochise, etc in the American films, Gilbert Mair, Rewi Maniopoto, MacDonnell, Titikowaru, von Tempsky, etc in the New Zealand films, sometimes as themselves, sometimes slightly disguised). Like all the stills from The Te Kooti Trail with the exception of those of Te Kooti preaching and Peka manipulating the cross, these are all outdoor shots, illustrating Hayward’s dominant use of exteriors rather than interiors – in part occasioned by budgets too small for substantial sets, but suggesting more than this, an affinity with the outside scene, shared of course with the early westerns Hayward knew, but also a prefiguration of a constant of New Zealand cinema fifty and more years later even when not connected with a genre of skirmishes and battlefields. Many of the stills used from Utu (Redux) and The River Queen, where the great Whanganui River is a dominant player among the cast, inherit this generic rather than merely pragmatic necessity of Hayward’s and his source James Cowan’s bicultural feeling for landscape as in the great passage from the opening ‘The Old Race and the New ‘ chapter of Cowan’s The New Zealand Wars -“Yet the passionate affection with which the Maori clung to his tribal lands is a quality which undeniably tinges the mind and outlook of the farm-bred , country-loving, white New Zealander today. The native-born has unconsciously assimilated something of the peculiar patriotism that belongs to the soil; the genius loci of the old frontiers has not entirely vanished from the hills and streams……” This characteristic is also found in all fifteen of the stills printed from the second Rewi’s Last Stand (1940).

The great Whanganui river, a dominant player in the film.

Apart from many other film frames from Utu, River Queen and Rain of the Children in particular, there are other notable illustrations : one of James Cowan at work above (no need to look further for that desired stamp’s design!); the splendid photo of a group of soldiers with General Duncan Cameron standing casually hands in pockets that so impressed Keith Aberdeine in his research on Cameron for The Governor. Also reproduced is Hayward’s fullblooded publicity poster for The Te Kooti Trail which packs in so many important aspects of his aesthetico-commercial duality – “Coming like a meteor … See it if you have to be carried there”; optimistic pride in the possible local industry “TO SHOW THE WORLD THAT NEW ZEALAND CAN MAKE A PICTURE”; the appeal to, and competition with, the more developed Australian industry “[Te Kooti] Greatest of outlaws and bushrangers …More fascinating than “The Kelly Gang”; and even comparisons with Hollyood epics “The Most Talked of Production Since ‘The Ten Commandments’ ” Also the invoking of historical facticity -“£70,000 and 300 Lives being lost in fruitless efforts to capture him….He was finally pardoned in 1888 by Act of Parliament ….”; and even a moral appeal to local patriotic feeling “You will be a much better New Zealander for having seen it”. One should mention too the photograph facing the opening of the Introductory chapter, a large posed group taken near Whakatane of the cast and crew of The Te Kooti Trail in 1927 from the Hayward Collection at Nga Taonga Sound and Vision, with connotations highly informative about the book and its subject. The open countryside grouping is in line with Hayward’s exterior location shooting remarked on above. Hayward himself with megaphone and cameraman, Ted Coubray stand by cameras, surprisingly formally dressed: (did they slip on more formal attire for the photos or did they dress more relaxedly while filming?) The main small group bookended by Coubray and Hayward sit, Hilda Hayward next to the “friendly “maori romantic leads, who are next to probably Arthur Lord and Billie Andreasson, and, I think, Tom McDermott, playing Gilbert Mair, at far right next to Hayward. Writing this piece in the Northumbria of the film’s beginning, I can’t check whether I’m right or wrong with the most difficult of these identifications, but if – as it should- the book ever goes into a second edition, Annabel Cooper could add the details. Behind the group on horseback are the Ngati Awa who played Te Kooti’s followers, including Te Pairi Tuterangi who played Te Kooti. There’s a doubleness of implication in the extended grouping. On the one hand it is democratic and biracial (even in some respects bicultural), mixing together Maori and Pakeha, while on the other, its grouping of the sitting “friendly” Maori and Pakeha is surrounded in a somewhat minatory way by the unfriendly followers of Te Kooti on horseback , suggesting threat (of course acted out in the film in the siege of the mill and the killing of Monika). Other illustrations particularly worthy of note are, in the section on Utu, the shots of Anzac Wallace – Te Wheke in the film – being arrested at Bastion Point and as the local union leader in the documentary The Bridge:A Story of Maori Men in Dispute; the pa graphics from Belich’s The New Zealand Wars; a photo of the legendary von Tempsky from the Alexander Turnbull Library;and from the chapter on Rain of the Children photos of Rua Kenana by George Bourne and James McDonald.

The many footnotes in a separate section at the back of the book are worth a detailed read through on their own, containing as they do not just textual sources but much fascinating information. A few particularly striking instances: – the references to Chris Pugsley’s and John Gates’ disagreement with James Belich over the claim that Maori invented trench warfare; reminders of Hayward’s first wife, Hilda Hayward’s, neglected role in Hayward’s productions; extra information about the censorship of moments in The Te Kooti Trail and Hayward’s reaction to it, as well as about Maui Pomare and Apirana Ngata’s correspondence over the film; a couple of footnotes concerning Hayward’s relationship with Gilbert Mair, about their first meeting and about later revelations of Mair’s somewhat ambiguous attitudes. The references to interviews (some of them conducted by the author) with Geoff Murphy, Keith Aberdein, Vincent Ward, James Belich and others, as well as to drafts of scripts, are a testament to the thoroughness of the research throughout the book, another instance being Cooper’s consulting of Melissa Cross’s thesis on the 1940 Rewi’s Last Stand’s score,with its evidence, derived from cues in Alfred Hill’s score, pointing to missing scenes in a film irretrievably cut to not much more than half of its original length.

Cooper writes at proper length on Vincent Ward’s fascinating and still too little appreciated River Queen, filling in considerable detail about the trials the production endured. Cut off from the local press coverage that would no doubt have better informed me, I had always imagined that the winter setting on the Whanganui River was a conscious aesthetic choice, that preferred its marvellous winterlighted vistas to those of summer. One of many passages throughout the book in which Cooper exhibits visual sensibilities that show her to be as much cineaste as historian, is a celebration of the look of that landscape. The explanation is that, prior to filming, Samantha Morton unexpectedly took on another role, which caused production delays, and because international funding came with the proviso that it had to be used within the tax year, winter shooting with its hardships was the only solution, but one bringing major problems, not least when Morton fell ill and returned to England for six weeks in mid filming, along with her tense relations with some members of the cast and then with Ward with whom she eventually refused to work. But because she was now essential to the film’s completion – many scenes involving her had already been shot – it was Ward who was fired (though reinstated for the editing). Cooper relates all this with intelligent restraint, even finding some empathy for the excellent but disruptive Morton having to deal with working conditions of a kind she had never experienced or imagined.

I find it curious that no writing about the film, even the very best, e.g. Roger Nicholson ‘s

two essays -‘ History, Love and Genre in Vincent Ward’s River Queen’ and ‘Vincent Ward’s Taranaki War, Battle,Captivity and Romance in River Queen’, has fully taken in the most audacious of the film’s tropes, the one which enables the narrative to end peacefully. Cooper almost seems to recognise it, but then leaves the subject abruptly. In it Ward and his co-writer Toa Fraser fused Belich’s revisionist interpretation of Titokowaru as peacemaker as well as great general with Cowan’s explanation that his mysterious failure to fight at Tauranga-ika was the result of allies withdrawing support because of Titokowaru’s ‘s adultery with an allied chieftain’s wife.

Melding revisionist history and Kimble Bent’s compelling anecdote as reported by Cowan, the film-makers invented the extraordinary fiction of Te Kai Po secretly plotting to avoid a war which would stretch disastrously beyond the winnable single battle at the Tauranga-ika pa, by indulging his known weakness for women, in order to deliberately precipitate a crisis that would drive away his allies, thus making the continuing of his war impossible. This invention, relayed through Titokaworu’s gnomic utterances and connected images of water, violence, blood and sex, first in the sequence where Titokoaru has his vision part shared by Sarah / ‘Queenie’, and then again near the end of the film is, perhaps representatively, misunderstood by a critic who, caught up in a thesis of ornamental “touristic” shots deriving from “Heritage Cinema”,imposed on the film, complained of a key image, that “an artistic shot of Te Kai Po copulating majestially with another chief’s wife, framed by rafters as the camera swoops above, briefly interrupts an important action sequence” (Olivia Macassey, ‘Cross- currents: River Queen’s National and Trans-national Heritages’ in the collection New Zealand Cinema: Interpreting the Past). Does this suggest that Ward’s pattern of verbal and visual allusiveness and oneiric premonitions is too subtle to be grasped? Or was the thesis-grabbed critic too distracted by theory to note the local effects? The latter, I think, though one cannot deny that the two parallel sequences are complex and difficult : the first, Te Kai Po’s vision, parts of which are shared by Sarah, with its fragmentary images of a red flag in the water, turning to blood, Te Kai Po having sex with a young woman, hongi-ing with the older chief ( given in fragments and out of the order in which we see them later when the prophetic vision is fulfilled and linearly clarified). In this second sequence, the puzzling, disjointed fragments, recapitulated and rearranged, become parts of a micro-narrative, the half naked skipping girls luring the soldiers, Te Kai Po’s allies arriving, the woman with whom Kai Po has intercourse seen among his allies, the hongi with the older chief, the shot of Te Kai Po having sex with the woman (which annoyed the critic quoted above), the chief taking her away and swearing at Te Kai Po, “you fucking bastard so this is what drives you”.And in both sequences there are verbal statement of a gnomic but eventually readable kind, e.g. “through woman I must challenge death”, and, as his allies depart, Te Kai Po’s slightly cryptic rejection of Wiremu’s “we could have won the day” with “The battle yes. But winning the war? Never” and his “Let my people go”. Though it must be admitted that this clarifying second sequence is made more difficult by being enclosed within battle skirmishes and the capture of Boy.

The production’s many troubles give rise to some meditations on the problems of the new era of international co-production in New Zealand film making epitomized by River Queen, as a historical film, the most expensive of genres. Describing how its American and British funding filled New Zealand shortfalls, but how the necessity of using bankable overseas stars placed ultimate power with the overseas funders, Cooper quotes Gaylene Preston on Utu to the effect that the shortlived tax shelter filmmaking boom (usually but too simply seen seen as wholly negative, though it produced numerous major films as well as worthless and stillborn ones) enabled what was a largescale – by local standards of the day – film to be made without overseas stars, and thus seemed “a brilliant moment”. Though, as Cooper aptly notes, with the clarity and economy that marks her writing, that after the decision not to adjust the tax shelter to keep out the offshore companies whose use of it had become notorious, but instead to remove it altogether: things went downhill. “Once it was gone the possibilities of a national film culture changed: smaller-scale dramas were feasible, but large-scale historical film could only be made with an international budget, and with the kinds of constraints that international financing placed on production.Utu was the child of an important moment , but it was born of economic circumstances that have not recurred since” (and, one might add, almost certainly will not).

One cavil I have with Cooper over River Queen, is her not picking up on Roger Nicholson’s two excellent articles on the film, only one of which is listed in the bibliography, though they deal subtly and persuasively with historical and genre interpenetration, very relevant to her chapter ‘Encounter,Romance and Conflict’, even if the second ends with a plea for a history film structured along the overt metacritical and self interrogative literal authorial presence lines of Ward’s Rain of the Children. Though Ward certainly makes it work in that film, it seems to me as regards historical film a general principle as sterile as the theorising of the 1970s which saw similar strategies as the only acceptable way, with predictably tedious results.(Try to imagine Utu reworked in this mode). Another point which seems to be neglected in the film, despite the general sense of the place of Romance in it, is the significance of the echo of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (A Midwinter’s Day’s Dream?) when Boy (Sarah’s son) takes on an Ariel like role as invisible to them in a tree he ventriloquistically torments Baine and his soldiers, as Ariel tormented Stephano and Trinculo in The Tempest.

‘Reenter Ariel, invisible, with music and song’. Boy in River Queen.

In conclusion it should be said that Cooper always writes well over the long stretch of what is a big book. If one chooses one instance to highlight this it might be this from her writing on Belich’s New Zealand Wars documentary ( otherwise neglected here for reasons stated above):

Belich projected a large onscreen personality and he attracted viewer attention……It was almost inevitable, therefore, that Belich’s own persona became a central component of the production, and that he would have much to say. He was declarative and intellectual: he drew viewers into the historical arguments by setting up received wisdom and then chopping it down. Emphasising points with his hands, Belich sliced the air to push home his points.The hands gained a minor celebrity of their own, and his onscreen and voiceover presence quickly became syonomous with the series. As he trounced implausible or self-serving versions of ther past, he marched across rural landscapes rather than sitting in front of academic bookshelves: this was an active, outdoor screen persona. The story of the [his] summer job digging trenches on the set of The Governor – a story that Belich told at the end of the final episode – pitched him less as a remote aceademic figure, and more as an accessible, if well-informed, bloke next door.

Here the historian-performer is read persuasively in terms of screen semiotics. It is clear that Cooper as historian largely agrees with Belich’s readings of the Wars, but here, restricting herself to the visually constructed persona, plays it out in terms that could be deployed affirmatively or negatively, but either way are splendidly accurate. Elsewhere and pervasively her writing is admirably lucid and disciplined, incorporating easily a wealth of research, reading and thoughtful viewing. There may be writing, and no doubt will be, on individual subjects in the book more imaginatively forceful than hers, but none, I would venture, as comprehensive, making her account of “The New Zealand Wars on Screen” indispensable to the degree that no future serious engagement with the subject could take place without constant reference to it, which is as much as any critical work could hope for.

Filming the Colonial Past: The New Zealand Wars On Screen by Annabel Cooper is published by Otago University Press.